Breastfeeding is beneficial for all babies, but according to new CHILD research it may have greater effects among infants living in contexts of lower socioeconomic status.

As reported in their paper in Frontiers in Public Health, CHILD researchers have found a stronger link between breastfeeding and improved child behavior scores among children living in households of lower socioeconomic standing.

“Because both breastfeeding and socioeconomic status have been linked to mental health throughout childhood,” observes lead author Dr. Sarah Turner, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Manitoba and Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, “we wanted to investigate whether breastfeeding modifies the association between low socioeconomic status and increased behavior problems.”

Using data from over 2,000 children in CHILD, the researchers analyzed measures of breastfeeding duration and breastfeeding exclusivity, as reported by mothers in the first two years following their children’s birth, as well as child behavior problems at five years of age.

At Study participants’ five-year CHILD visit, behavior and emotional outcomes were assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist questionnaire, completed by a parent, which includes questions about inward-focused behavior like anxiety, fearfulness, and depression, about outward-directed behavior like aggression and hyperactivity, as well as questions about sleep-related and other problems.

Researchers classified households as being of lower socioeconomic status (SES) if one or more of the following characteristics applied: it was a single parent household; it was a household with low income; or the mother’s education was below college or university level.

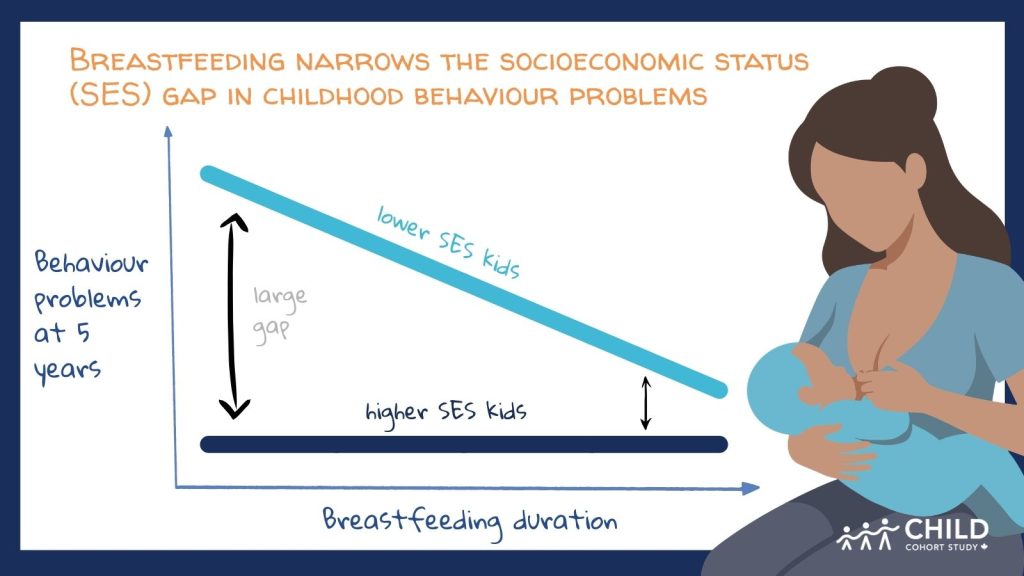

Based on these data and criteria, the researchers found that on average, children growing up in lower SES households had more behavior problems than those in higher SES households. But the difference between these groups narrowed when children in lower SES families were breastfed exclusively for six months (that is, without formula or other foods) and for a longer period overall.

“In fact, in the higher SES group, breastfeeding was relatively unrelated to behavior scores,” comments Dr. Turner, “while in the lower SES group, there was a clear relationship between more breastfeeding and better behavior scores.”

“This finding shows us that breastfeeding may be one factor that can help ‘close the SES gap’ in child behavior scores.”

However, the authors note, those living in lower SES environments are precisely the populations that tend to experience more significant barriers to breastfeeding.

“For breastfeeding to be a possible choice for all families, policies and programs that reduce barriers to breastfeeding are crucial,” observes senior author Dr. Meghan Azad, who heads the Manitoba Interdisciplinary Lactation Centre (MILC) at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba.

To help reduce these barriers, Azad and Turner have partnered with colleagues at MILC to launch a free breast pump loan program for families with limited financial resources. They are also advocating for expanded insurance coverage of lactation support services, which are often financially out of reach for lower-income families.